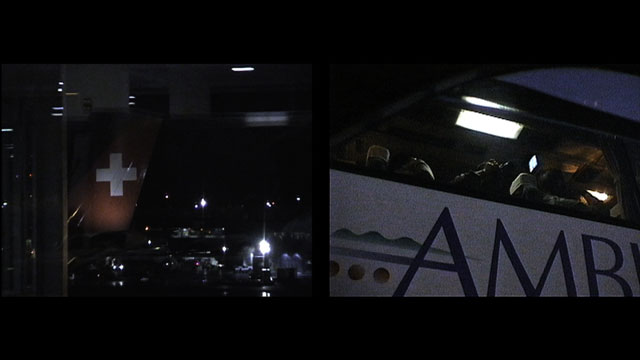

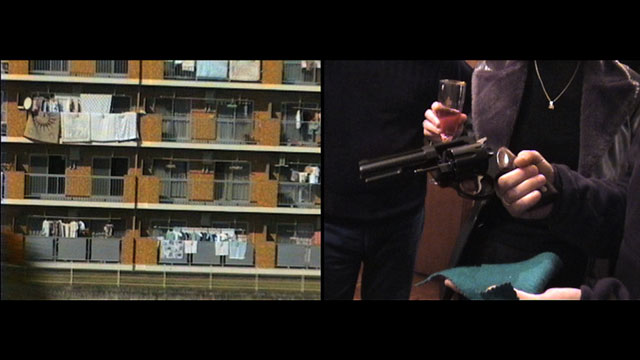

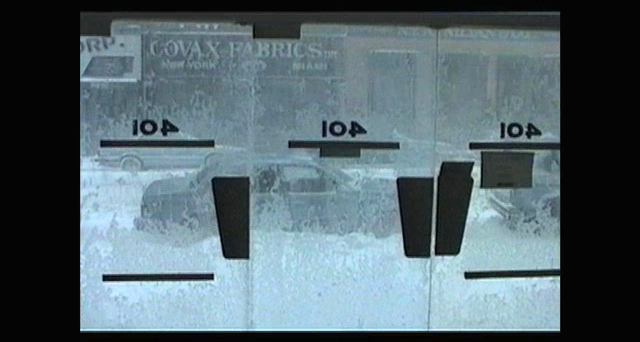

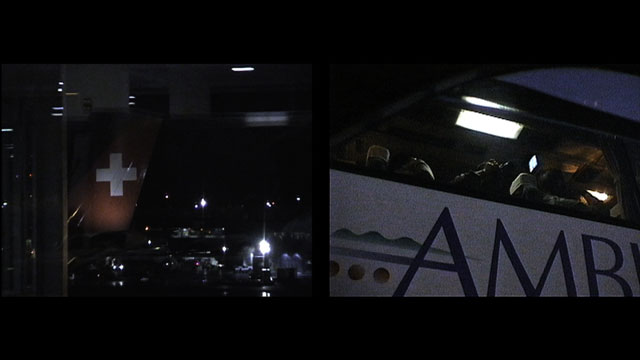

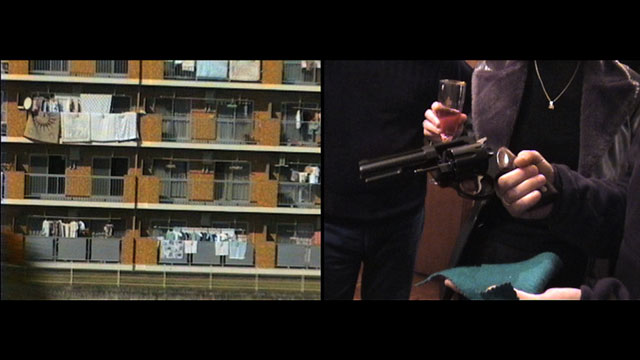

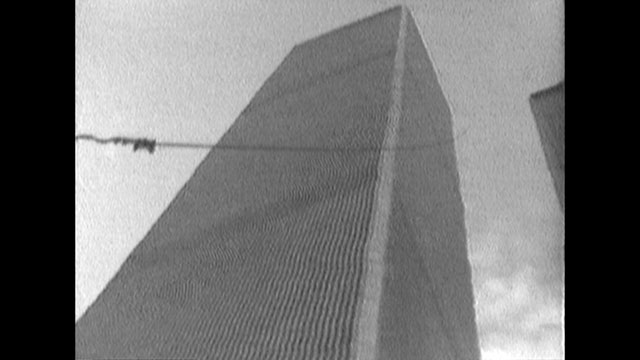

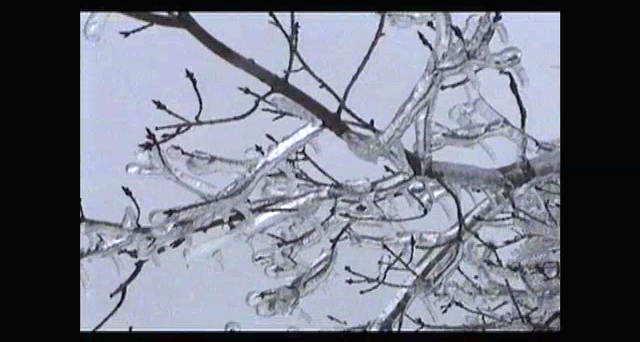

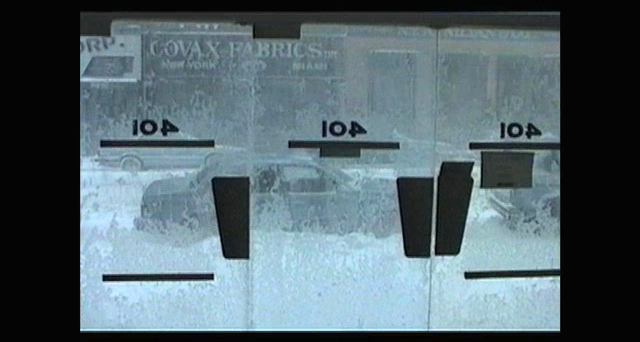

50 stills from the 'The World Out of My Hands' (2006) selected by Michel.

50 stills from the 'The World Out of My Hands' (2006) selected by Jesper.

All Images © Michel Auder

Back to top

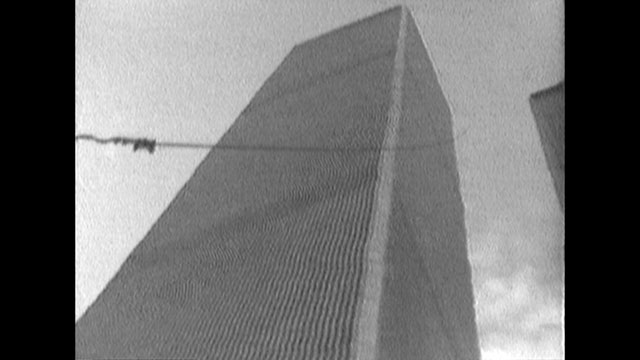

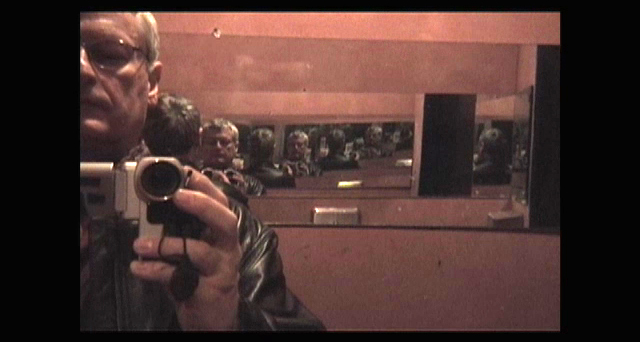

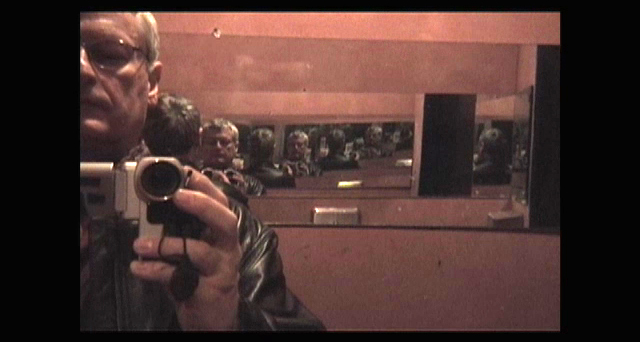

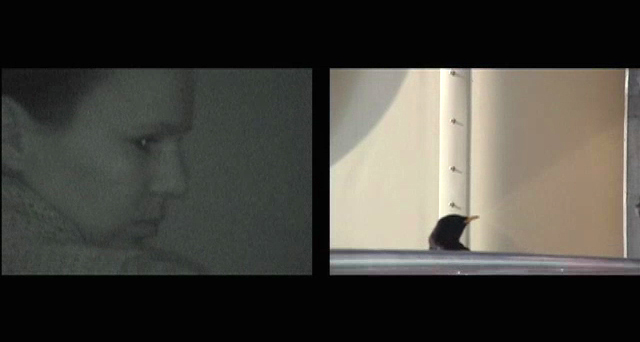

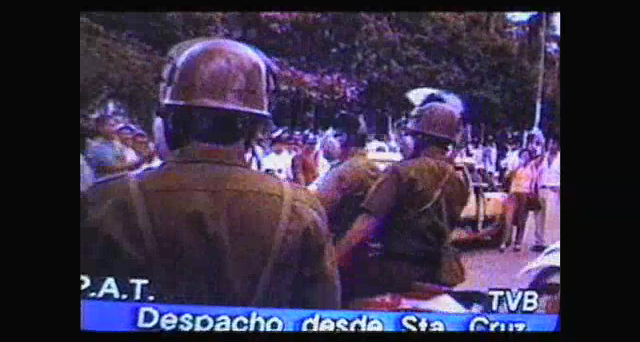

So, we are going to talk about "The World Out of My Hands". Michel Auder: Right. Jesper List Thomsen: Do you fancy doing a short description of the piece? MA: Well, I mean, I don't know exactly what it is, so... We can find descriptions of the work here and there by other people. What I think? I was having a show, so I was challenged to make a work and I am at that point 3 or 4 years into experimenting and finally grasping the entire editing software thing, I didn't need to call somebody to ask; how do you do this? How do you do that? Finally I am very comfortable with it. It has become a lot more solid and doesn't crash on you. In 2000 it was kind of a mess. So this is the point where I decide I am going to make a new piece, go through a lot of the video footage and look at my observations on my travels around the world, and see if I can analyse it somehow and put something together that represents my kind of viewpoint. I guess you could say poetical viewpoint in a way, meaning not conventional. So, it is not really written black on white what it is about, the viewer should be feeling my observations and it becomes my political looks at things. JLT: Maybe in an abstract manner? MA: Not abstract, but poetic. Abstract, no. I think it is realistic, you know, but that is debatable. JLT: I am kind of thinking, the title, "The World Out of My Hands" suggests that the camera, which you hold with your hand is obviously the device with which you record, but it almost sounds as if you are not using your eyes, that the hand is just recording pretty much everything. And, I was wondering if one could suggest that the hand is more honest then the eye? MA: Well, I don't think so. I think the eye in that case is very important, so it is like the opposite. I didn't just put my hand out there and trust my hand. The title "The World Out of My Hands", it means to me that I cannot control the world, it is out of my hands. It is beyond my power to change it, people or myself, I mean, myself is more in my hands. Also of course out of my hands because the camera is in my hand and my hands are working, but I think my eye is the most important and my hand just a tool holding another tool. It is all in the vision and editing. JLT: If one looks with the eye, how does one deal with or do you believe in such a thing as an honest piece of work? Or an objective piece of work? Where do the eye and the subject stand in terms of one looking at the world? MA: Well, I am not interested in objective work. I don't believe there is an objective work, especially when using a camera and editing. There is more objective and less objective, when it is more objective you could call it good documentary. I use the documentary style to record, but then I look at it, I cut pieces out, I edit and I mix it with other images other sound. It is more to bring the vision of my eye and what I think and not to be objective. I am working generally in the opposite way, I never think my work is objective, it is entirely subjective. JLT: So, the subject or the artist is totally integral to the narrative somehow? MA: Right, you know, I cut, I juxtapose one segment with another. Once you put one shot next to another it starts to mean something else. You might see the same shot in different contexts and it takes on a different meaning. J LT: So, that is the process of editing? MA: The process of editing and juxtaposition, you can see somebody crying for a different reason, because of pleasure or because it hurts. This is the simple explanation, but it is like the World Trade Centre that seems to be burning reminds you of the of a World Trade Centre that is burning because we know what happens at the end, but I actually never filmed it burning they are clouds tearing into the towers. JLT: So it refers to a collective memory of events? MA: In that specific example yes, but then it goes on. When one makes a film it is rarely objective. JLT: At a very early point, in fact in the very first shot, you introduce the cameraman or the voyeur. You are introducing yourself. You are standing in what I think must be a toilet. MA: Right. JLT: And you are zooming into the mirror and there is a back and forth reflection that infinitely multiplies your presence. At the same time the soundtrack is of somebody taking a pee I believe. MA: Right, right. JLT: And the shot to me looks as if it is the duration of that person taking a pee. And, I believe that person to be somebody other than you, as it doesn't look like you are peeing at the time. MA: Right. JLT: I think that is quite an interesting beginning. There is this possibility of the self-portrait, but then the soundtrack and the length of the shot seems determined by an action beyond you and your control. MA: Right, I mean. It is interesting. See, this is an ambiguous work and I kind of like the idea of you telling this story. As a matter of fact I am taking a piss, I am in the bathroom taking a piss and I am filming. But, that is the beauty of making film, I manage to be so non-objective and then you bring your interpretation to it and that is where becomes interesting for me. But I don't want to intellectualize my shots, I did it when I did it and that is the point. JLT: Then, I will tell you how I encountered the piece. MA: Right. JLT: Which, I did in a museum in Copenhagen. I knew of you and I decided to watch the piece. It is about 42 minutes long, which is relatively long for a museum installation, but I sat through it and I really enjoyed its poetic value. I travel a lot myself and this idea of constant movement is something that I can really relate to; the encounter with places and the juxtaposition of experiences and so forth. But then at a certain point there is a shot of two girls sleeping on each other's shoulders and I immediately realised that they are friends of mine and I was like "wow!" I haven't seen these girls for maybe six years and there they suddenly were, it took me totally by surprise. And I soon realised that I, myself, was in fact sitting in that same room. I wasn't being filmed, but I was present. MA: Right. JLT: So, there was this experience of, you know, how you might say that you find yourself in a work or identify with a work. Well, it was kind of interesting because I totally got into the piece because of its movement and transit qualities, but then after a while I literally found myself, I was physically present without being physically present, but you know, I was sitting in the room. MA: Right. JLT: And I thought that was quite amazing, quite special somehow. And that is why I thought it would be great to talk to you, it seems like this peculiar coincidence. MA: Right, (laughs), yeah. I mean, there is nature and people in there and the observations are probably worldly enough for everyone to find himself or herself in someway. But you came for real and maybe you are in the footage that is not there, because there are close-ups of a lot of people, and I was choosing specific images. JLT: But there is this possibility of encounter, which I find really interesting. MA: Right. JLT: And for me that is what this piece is a lot about, the possibility of encounter no matter where you are. You could be on an aeroplane, in a train station, on a street in Russia or in a field in Denmark. There always seems to be the possibility of finding beauty or poetry in the encounter with everything or nothing. MA: All those images are real, I didn't make them up they actually exist. I am recording not because I find it enjoyable but fascinating to show the way our world is at that moment. It is just my vision of things, the way I cut things together, what I see in daily life, my observations of culture. It is looking at our generation with the perspective of time and experience. JLT: Do you ever start a work or do you only finish a work? MA: I start it with an idea, which is I am going to travel through my own travels and capture a certain vision of the world. And then it ends when it ends. I work in 2 or 3 different ways. One is recording things with a work in mind, the other is this should be recorded, I should capture this and lock it onto my shelves with certain notes telling what it is about - like people dancing on island - clouds - or faces of sculptures recorded in church. They are what I call my vocabulary of images. I start a work with the editing process quite often, where I look at my work and say this is interesting, this is bad. JLT: Have you ever made a piece where there is no editing involved? MA: In-camera editing only? Right, it has happened, especially in the 60's. Still I was editing and cutting 16 mm, but it was much more composed as I was going on. A film shown last month in Cologne at the art fair called "La Plage" that was made in '67 and made totally in the camera. JLT: 16 mm? MA: Yeah. JLT: I suppose there was a different idea of time with 16 mm than video. MA: Yeah, but that doesn't mean I shot video like hours and hours for the hell of it. Of course I shot 6,7,10 minutes at a time, but I always felt restricted because of the 60's where I worked on film, I come from that time. So, even though I have a reputation supposedly that I point and shoot, that is not what I do at all. I will use that possibility when it is worth it, but it is not like it is going on all over the fucking place and, whatever, maybe tomorrow I will look at it and get something good. It has never been my principle of shooting and I don't like this idea. Unless, like Bruce Nauman who leaves his studio and there are mice coming in and dance around and everything. That is a magnificent work, its great, like the whole night you see the cat coming by and things are falling off the shelves and so on. JLT: That piece is almost a total opposite to "The World Out of My Hands". There is no movement; at least the camera is totally fixed. MA: Right, exactly. JLT: It is a nice contrast. I read somewhere that you don't think of yourself as a voyeur, but rather as a participant? MA: I never thought of the voyeur as somebody that would be possibility. Not that I haven't used that system once in a while and even got off on it because it can be a very valid situation. But, I am not a documentarist, I use a documentary style and I am not a voyeur but I use a voyeuristic style. Meaning I am kind of a little removed and I kind of disappear, but I am always right there in the middle of it. I am looking at my own race and studying them, but I am in the middle of all those people, like in the Chelsea Hotel, I even marry them, I even have children with them, and, I divorce them, then I go to another place and I fuck them, so we are mixed. The voyeur is somebody that is never there, someone who is just looking from around the corner. Once in a while I have been a voyeur and been interested in being one, but it is a rather minimal part of my work. People think I am in my work all the time, but actually until 1995 I am not there physically at all, but I shot so much that I am in my work all the time. But, in relation to the 5-6-7000 hours of video I have here in the studio I am not really in my work, but of course it is me. JLT: Do you think you are a performer then? MA: I am more like somebody that comes into the world and observes it, then, because I am a human I get involved with these people. JLT: There seems to be an element of a lived-experience. MA: Yes, I go to a place that I don't really have much knowledge of and I live with the people. There is very little voyeurism in this, almost none. JLT: The last shot of "The World Out of My Hands" is of kids playing. There is a sense of joy and naivety about this scene, was that a deliberate choice to let the kids finish off the film? MA: It comes by itself, it is not planned from the start, but the shot pans over onto canons and chains. It is actually in Finland on an island off Helsinki. I hanged around, took a boat there. Old Canons were displayed around a church. The pan goes from kids to chains to canons, that is very symbolic, chains, we are not free and whatever. I don't want to be to heavy, but actually that is what it means, they are playing near canons, but it is not me it is the fucking situation that is like this and I just see it. But the main thing is they are children going "lalallala" saying words I don't understand, which sounds similar to all children in the world. JLT: A last thing that would be interesting to talk about is, when we spoke on the phone last week to arrange this meeting you said that you would be away over the weekend, and, you said "if I die and do not make it I will send you an email". MA: Right, that is a good end. JLT: How do you think the process of recording is related to the idea of death? MA: I just use it because I am like ... That is the way I live by exploring my surroundings, the life that I am living. But, I don't think I am that interesting, I think the world is interesting and I am just describing what happens when we are about the way I understand it. What was the question? Ahh, death. No, my recordings are survival it is the opposite. It is a means to survive, it is a means to be me and it is a means to explain my experience of the world. |

|---|

Michel Auder is an French/American artist based in New York, USA.

Jesper List Thomsen is an artist based in London, UK.

50 stills from the 'The World Out of My Hands' (2006) selected by Michel.

50 stills from the 'The World Out of My Hands' (2006) selected by Jesper.

All Images © Michel Auder

Back to top