Adam Gibbons: I'd like to talk about your work Make No Mistake About This , 2007. I'd also like to discuss your use of moving image more broadly, especially its relationship to sculpture and the sculptures that you make.

Maybe you could start by describing the work and the process of making.

Wolfgang Plöger: The starting point was the text itself. I downloaded some of these last statements of the death row prisoners when I did an image search with Google some years ago. It took me some years to find a way of dealing with them. I had them in my studio for a long time and I kept coming back to them. These statements are very emotional and strong. On the one hand I looked for a way of showing them. On the other hand I did not dare to print them or to write them on a wall.

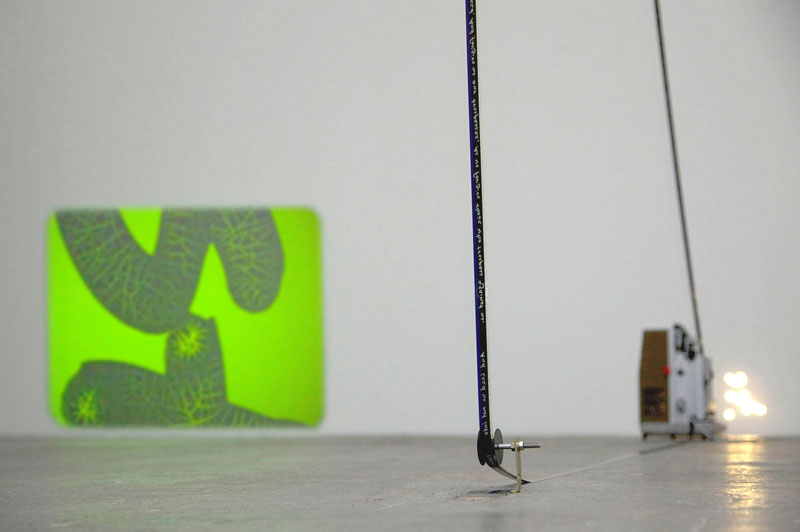

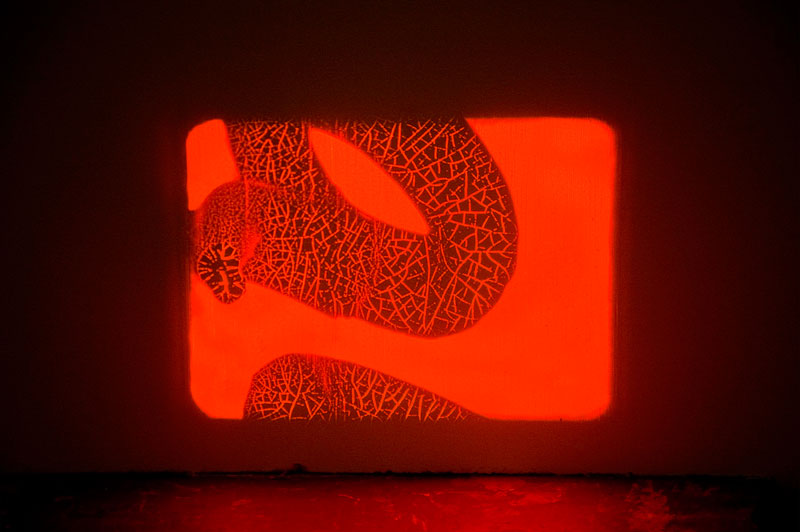

Then I wrote them down on clear 16mm film leader material. In the projection you only see flickering lines, but you can read the texts on the film loops themselves in the exhibition space.

When a visitor enters the room I think the focus is always on the projections. So in the beginning it seems that there is nothing to see. After a while people start reading the writing on the film material. The projection seems only to fail.

AG: I wanted to comment that film is designed to be exposed to light, from which it takes an indexical copy of whatever is in front of the camera. As you've described, in this work you wrote some of the last words uttered by prisoners on death row in Texas directly onto the film. One of the characteristics of incarceration is that of invisibility, keeping something, the perpetrator of a crime, hidden from public view. By inscribing onto the surface of the film that constitutes Make No Mistake About This , this invisibility is disrupted. I wondered if you could comment on this act of making visible?

WP: There is a conflict between the film material, where you can read the text, and the projections, where it becomes an abstract flickering. Maybe I found a weak point of the medium itself.

The installation is balanced between visibility and invisibility.

I make a lot of animations based on drawings. When you make animations you always calculate the difference from one drawing to the other. That's what the whole thing is about. You move step by step into the unknown future of a film. But in the installation that we are talking about, no frame is related to the next one. The projector just cuts the text into fragments.

Returning to the aspect of incarceration, you are right. We hide these criminals behind thick walls. But at the same time we focus on the crime itself. Our newspapers and movies are full of that.

I mean it is disgusting what some of the prisoners did. But in these last statements they show that they are still human beings. Lots of them pray and apologize. Through these statements they come very close to us. I think that's why the statements are so complicated. I mean emotionally. (Also for me.)

AG: It's almost too much?

WP: Exactly, it can be quite Kitsch in a way.

I was in an art school recently giving a talk and one of the students, a woman, was really condemning the work. She said, "it's really stupid, you just take this text and that's it, it's too easy". She found the work a little bit unserious in that way, that all I do is write it down and then it's my work. It meets with a lot of contempt with regard to the emotional situation of these people, the moral situation of these people. She felt maybe it was kind of an abuse of them and what they're feeling. (And of course) I can understand what she meant. It's quite easy to see it like this, it's quite easy to take something like this and show it with images and you can cause quite a scandal. And maybe that was my problem with the text, that it can affect or it can get people quite easily.

AG: In the pamphlet accompanying the exhibition at Kunst Werke you stated that you found the prisoners' final words on the website for the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. If they pursue the link, the audience can find out the details of the crime committed by the accused. They can even see their photograph. The idea of the Internet as a possibility, a potential source of work, is one you've touched on elsewhere. Was it your intention that the prisoner should be discovered in this way?

WP: When I realized the first pieces that had to do with death row inmates some years ago, I called the whole show Meeting Tom . That title was close to Peeping Tom . And that described how I felt at the time about getting all these images and information from the Internet. I felt a little bit guilty. But now, after some years, I find it quite normal to do so. That's in a way the typical use of the internet.

I'm not a journalist who researches a topic and later reveals something to the public. It was my intention to confront people with these specific texts that I chose, and in a specific situation. I did not reflect so much on the question of how people would deal with it later on. I use the statements in a more isolated way, standing by itself. More as a piece of literature.

AG: Although the work implicates prisoners everywhere, the prisoners you focus on are all in the United States.

WP: Someone asked me once whether the work is specifically related to the United States. Of course until some months ago, while Bush was President, it was very easy to criticise America for a number of different things, Guantanamo Bay for instance. But at the same time I'd say that whereas many states have the death penalty, they also provide this information. If you take the example of China, there are all these people executed without any information for the public to look at. Nobody even mentions their names, there's nothing from the trial, there are no last statements... It's not a direct criticism of America.

Just recently I recognised, that these prisoners and death row inmates became this quite abstract community for me. I haven't contacted these people, I hardly know anything about them, they are just the images that I've been using to make some installations in different ways.

AG: So you used images of the inmates, too

WP: At first I was merely looking for portraits of these people. That was the starting point, and then I got the texts as well. The first piece was dealing with what you asked about earlier, to do with film connected to (sculpture or) photography. It was an installation I had in the Netherlands. I used maybe fifteen images and I printed them on an old black and white printer.

AG: They're from the Internet?

WP: They're all from the Internet and they're different sizes but very low resolution. I enlarged them just by copying them, so I had one copy of A4 or A3 or even bigger of each prisoner and then I reproduced them by drawing them, using transparent paper. 30 or 50 times, I don't know, it depended. If you see [the drawings] next to each other they look the same, but of course there are slight differences. With the small ones you can still see what you draw but the huge ones become so abstract you can hardly see what they're about; its only dots and dots and dots and dots. So I reproduced them and then I made an animation from the drawings of each prisoner.

AG: Do you have a purpose for this?

WP: The idea was quite simple; to stretch a photo into a film piece. But I didn't really film them frame-by-frame. What I made was more like a slide show. I filmed each drawing for about 4 seconds, then the next one and so on. So every 4 seconds it went "tack" and you always had the impression that the plot would go on; it's slow motion but you always expected something to happen, a development.

And that development seemed to occur; by these very slight differences which I didn't really control. Through the process you always had the impression that something changed, the face, the eyes, something. But in the end it was the same moment over and over and over again, and only through the reproduction of the work, the handmade reproduction, did you have the association of the film that was developing and echoing on. There were maybe ten or eleven projections in that room. There's this clack, clack, clack, always these changes around you, so it was not so static. And because you were always expecting something to happen, in the end it was not disappointing in that way but kind of, because it was perhaps only underlining this moment. There it exists somewhere between photography and film.

AG: I was struck by the difference of some of your work... there's this very political aspect to some works, for example Make No Mistake About This , then there are others. I didn't see the Transport Boxes for Shadows in the flesh, but for me they operated in such a different way, they are very preoccupied with sculpture and with formalistic, maybe philosophical notions of space, light and time in a way which Make No Mistake About This also deals with in some way. Time for example is very present in it, but there's such a different register in these works and I wonder how you feel about that.

WP: Yes, I used to have the tendency to do a lot of different things at the same time, that weren't really related to each other. I mean there are moments when something relates to everything else, when everything just fits like a puzzle and then... it's really hard for me to explain. I can't bring it to a point and say "this and this and this goes together, that's the main concept of my work. But you need five sentences to say "this is what I'm doing" and if you can't then you always run into difficulties. I try to ignore it. For a while it bothered me, but now I try not to pay attention to it and it's fine.

AG: Now you just have a studio with lots of rooms and you can put different things in different rooms.

WP: The sculpture in there, the film in here. Maybe that's how it works.

I would say my main thing has been animation for years now, because it takes so long to do all of these drawing. I have piles and piles and piles of sheets.

It still fascinates me that I get a film out of these piles of drawings, because the film has such different qualities. And the relationship between animation and reality is interesting. But I never really studied this and I know I'm not very good at drawing so it's still quite experimental (laughs). I can still discover a lot of things.

AG: And then with the text, the writing on the film, that again behaves differently.

WP: Of course.

AG: It doesn't indicate plot or movement or progression, like you say it works against that principle. You called it 'failed film' before.

WP: You know something's happening, you have this text and you want to show it or not show it. I went from working on a piece of paper and then filming it, to then making marks on the film. Suddenly the focus is more on the length of film and on its relationship to the projection.

I made, for example, a photo piece, where I cut out elements of slides. That's very similar in a formal way. People and Boxes I called it. I had a lot of slides in my studio. Found footage from second-hand stores. I cut out parts so the people on these slides were kind of put on light boxes. This changes the perspective of the whole image. People from the background seem to stand on a pedestal in the front as a miniature.

It's hard to imagine [the people] standing there. They seem to fly up there really. It's playing with these elements of the pedestal and putting a sculpture on it, and it's maybe more traditional in that way, the topic.

This slide work is more funny than serious. We're talking about stuff and images which aren't meant to be critical or political. But as I said, it touches Make No Mistake About This in a formal way. Without these cut slides I probably would never have had the idea to write down these last statements directly on the film.

AG: Similar to the portraits of prisoners which you animated, the words don't have an apparent progression because of the illegibility of the projection. Using the loop as an installation method, they become even more self-contained in a formal way. Referring back to the point we've already discussed, of issues of visibility, to what extent does this metaphor extend for you? Or is it more about a feeling? Or is it simply a device for installation?

WP: These last statements are very time-based, of course. The moment that the prisoner stops talking, he is dead. That gives even another meaning to the endless film loops, as if the whole installation could fix this moment of speech and avoid the execution.

Both installations have a ritual aspect. It's an act of appropriation to redraw these portraits or to write down these last statements dozens of times. There is the repetition of an action, there is the "power of evil" and maybe the subconscious wish to influence something. But these are reflections that came afterwards.

AG: Coming back to the installation, you looped the film in a primitive and very sculptural manner, emphasizing the length of the film and the space in which it was installed. Was this only a practical solution to installation?

WP: I use a lot of film loops in my work, so the idea for the installation came quite easily. The first time I showed the piece, I presented the loops on the ground. That made it even harder to read the text. And the film loop on the ground became a physical border. The technique is very fragile, so visitors were very aware of their position in the exhibition space.

The loops became very sculptural in that show, yes. I liked it. And it made sense, because I wanted to emphasize the presence of the length of film as a ribbon of text. Without the projections, it almost looked like a Fred Sandback piece.