'On Finding Time' (2009)

Image © Elizabeth McAlpine

Back to top

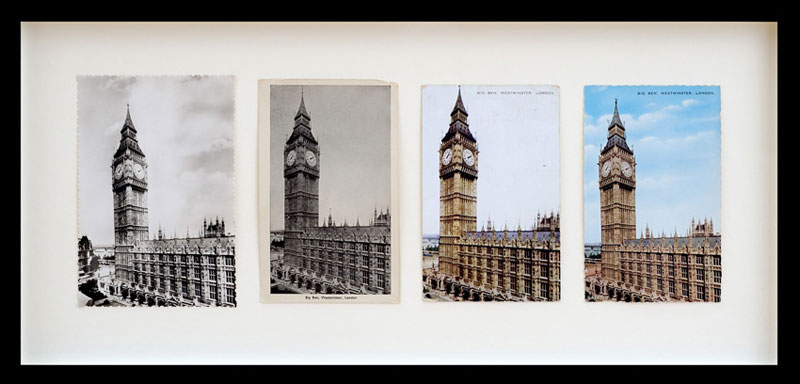

Adriana Salazar Arroyo: I would like to begin by asking you to describe the process involved in the making of Found Time (Big Ben). Elizabeth McAlpine: The initial idea was just to see how much Big Ben had been documented. I wanted to find published images with the authority that a postcard has,rather than using file sharing sites. The endeavour from the start has been about collecting every minute in twelve hours and it being a published/mass produced image, which then disseminates into the world. ASA: I wonder if you think of Big Ben as an authoritative Icon or as an object that is able to tell the time? EM: It’s something that is able to tell the time. I am interested in Big Ben as a structure that is a very definable pin point and that these postcards go out from there. For me, something happens geographically: this place ends up in other places. Big Ben is a structure that has been photographed since its incarnation, its history is documented, right from the start. Also, I like the idea that the clock on it gives a very linear sense of time but when you organise the found images in a linear fashion in accordance with the time that it [the clock] marks you get a complete non-linearity and this is what I am really interested in. ASA: This non-linearity operates in a similar way to the stuttering or staccato say, in structural filmmaking… EM: Yes, for me it is about that kind of stutter and also the blank spaces on the grid left by the minutes that haven't been found yet. Some people think about this work as being about an impossible endeavour and actually, I am not interested in that. I guess if I compare it to film the white spaces are the white flash frames that come in and realign the eye so it is able to look again. ASA: You could also draw a parallel with films that have a very fixed preliminary structure where shots often end up being very short. This structured fragmentation can allow for a sense of rhythm to appear... EM: Certainly this is happening with the postcards once they are put together. The work can become more and more like a film: you have the wide angle shot, the mid range shot and the close-up. Also, there is a huge amount of repetition of certain framings of the building and when they are lined up you have a real sense of movement through the space and time. You might find that there are three images sequentially, one after the other that are identical framings of the structure and its surroundings which is amazing, and then you get a white frame and then a close up... It almost becomes a story-board for a film. I am really interested in photographic repetitions of framings or repetitions within film work and like any collection you pull enough stuff together and you start to see systems, structures and patterns. I am always quite surprised by how quickly they appear. I reckon there are about seven or eight different framings and when you see a new one it is really surprising. ASA: What is it that interests you about the structures that seem to appear? EM: I don’t know, they make me feel safe. Although it is probably far more complex than that, I don’t know what it is, I guess they give me a silly pleasure. ASA: Might it have anything to do with the rhythm they produce or the kind of repetition that you can compare to the pulsing of the heartbeat for instance? EM: I think that there is probably quite a lot to do with that but there is also a thread through my work that has to do with collecting things and the pleasure that that brings. I don’t tend to question it very much, I tend to just go instinctively with it. ASA: Is this collecting related to a desire to possess? EM: No, it is about the discovery, the finding of another one in a hands-off manner, I don’t have an interest in making them. I like this of re-gathering… the postcards coming back to London I mean. I am not particularly interested by it being London. It is just a by-product of the fact that I happen to be here and I am British but it is not about Britishness, that could be misconstrued. I like the idea that these postcards have come from this city and they have gone out into the world and been sent all over and that I am re-gathering them back to one place. It’s quite funny that it happens to be London, but it could be Paris. When you see the stamp marks and dates you get much more of this sense of time and place stretching out and moving back. I am nervous of making that too explicit in the installation because it might become about nostalgia or a British patriotism or colonialism. You can’t help it when you are using such an iconic building, these things become part of its identity and its history but for me the interest is as simple as the fact that it is a clock that has been documented. ASA: I guess it is also a way of playing a game. EM: I think so. More with myself than with anybody else. Definitely for me it is a kind of game…. ASA: Do you see this work as a collection of frozen moments in time or as time that passes? I have also thought about this work being produced as a book, actually. This would be its ideal. Then the narratives that are happening on the back of the postcards become much more a part of it. Time moving through a geographical location becomes really apparent on the back of the postcards. EM: When I make films the materials that I find always dictate the length of the edits or the films are always placed in installation situations so I am never dictating a beginning or an end. I always expect people to come and go. With a series called Light Reading, found single frames are put together, the frames themselves are each edit. ASA: Do you then hand the choice to the viewer? Someone could spend half an hour looking at an image of a 'single' minute on Big Ben’s clock face? EM: Yeah, absolutely. ASA: So you are in a sense extending time or shortening it and you can only do this with still images, you couldn’t do it if it was a moving image piece. If you animated it you would be controlling the duration of each image. EM: If I animated it, each postcard would be a frame. ASA: Or a minute? EM: No, they would be a frame. Because a frame is a still and they are stills. I have thought about this. ASA: And it wouldn’t be a 12 hour long film? EM: No, it would be less than a minute... I am just putting quite an arbitrary structure on to it, it may not make sense to another person, maybe if it is a still that says that it is 10:10 then its length should be equal to the duration of the minute of 10:10, but I am really interested in disrupting all of these structures of time. ASA: Is that one the reasons why you are taking such an iconic time telling devise and then fragmenting it? EM: I think yes, I am interested in process and structure, and putting one form on top of another process, or one process on top of another form, if that makes sense. So if I were to animate the Big Ben postcards for me it is far more interesting that the time is re-organised in a way that is dictated by the material rather than by what the image represents. This seems to create a fracture and disruption, which hopefully makes us readdress structures and systems and creates a space to question why things end up the way they do. ASA: You have said in the past that you are drawn to film because it has the ability to materialiase time? Can Found Time (Big Ben) operate in a similar way? EM: For me it materialises time differently. For example in the single hour version there are two framings that are absolutely identical, apart from the fact that they are obviously taken years apart. The size of them is varies slightly but the framing is pretty much spot on; what happens by positioning those two things next to each other is that they are only one minute apart in terms of the clock face but a decade apart in reality and you have to make a mental leap. Even though it looks like a minute, there are also ten or fifteen years in between, a lot happened in between those two postcards. I think somehow it works better when it is exactly the same framing. EM: Found Time is definitely sculptural to me because it has an embedded sense of time that feels physical and weighty, it gives a sense of space. A postcard might only be a couple of inches on the plane but it feels much bigger than that, especially when it is placed next to other postcards. The work deals with a kind of three-dimensional space even though its presentation is two dimensional. ASA: Some minutes haven’t been found as yet… Do you think that these missing spaces are in anyway metaphorical of our relationship to time in London as a city? EM: Do you mean, that there is never enough time here? … The missing minutes could be metaphors for those kinds of things but they are more like stutters to me. The work is not a reflection about life in London. ASA: It is difficult for anyone who knows that you work and live in London not to make those associations. EM: I guess you have to let it be in the world and for those associations to be made. I am so consumed in it at the moment, I am trying to be objective but actually, maybe it is a response to living in this city, I certainly feel a different relationship to Big Ben now, than I did before. I don’t have a sense of Britishness with it though. I get more pleasure out of the clock face, I have always loved clocks on buildings. In London, they seem to always tell the wrong time, this really interests me and I don’t know how to capture it. ASA: It is an authority being mistaken that gets your attention? Does this provide you with some sense of freedom? EM: Possibly… This wrongness gives me real pleasure. These clocks are trying to be helpful but they are just not. They are so attractive as they appear so important, grand and institutional but because they are often wrong, they end up looking a bit silly. EM: The work makes itself. I am drawn to that, it also happens with the found footage work in relation to Hollywood. This feels like a side of the work that I haven’t got my head around as yet but maybe it implies a rebelliousness, although this is not my initial intention. ASA: Do you think that this is a problem that is inherent when one appropriates images, one has to deal with the history, one loses control? EM: Yes it absolutely is. Even with the Super 8 film sculptures, by putting a single piece of film through two projectors and making the loop so large that it goes all over the floor and getting the film scratched , I am not trying to be disrespectful to it. I am not really trying to break rules, I never had any rules in my life, I am not even concerned by them. As a teenager I could do whatever I wanted, there was no point in rebelling and as an adult I haven’t had to keep a job or lived in anybody else’s structure, I build my own structure. I don’t really feel that I am trying to break rules, just trying to do things that interest me and that I like. It just so happens that it comes around to me disrupting systems and structures but this is a by-product of me wanting to get somewhere or find something out. ASA: Is it that you are allowing something to happen? To me it seems as if you are concerned with the experiential side of doing something, of investigating? You may not know what is going to happen until you do it? EM: I can have a clear idea once I start gathering stuff together and it is not necessarily by accident that things get to where they are - it’s not quite as floppy as that but I am also quite happy to pursue things far. |

|---|

Elizabeth McAlpine lives and works in London. She is represented by Laura Bartlett Gallery, London.

Adriana Salazar Arroyo is an artist based in Berlin.

'On Finding Time' (2009)

Image © Elizabeth McAlpine

Back to top